Part one of this piece showed how insufficient collective moral responsibility is blinding Western democracies to the results of their actions. Part two looks at how this shortcoming in the social and economic realms undermines the West’s social contract from within.

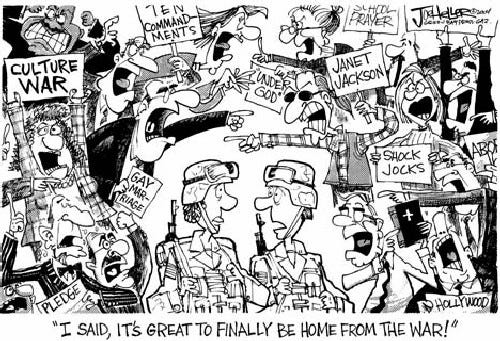

Legacy and independent media in the West are replete with pundits decrying a raft of issues ‘tearing society apart’. Identity politics, the migration crisis, social media, mental health, liberals, conservatives, China, and Russian trolls are all blamed, taking the limelight away from a truism that is too simple for its own good – It’s the economy, stupid.

The Western modern democratic social contract is founded primarily on the idea that elected officials are there to act in the interests of their electorates. Those interests vary from issue to issue, however one interest is common over time and demographics – the delivery of relatively increasing material living standards.

Western politicians are elected based on their ability to deliver that outcome before any other. They deliver that outcome in negotiation with the financial elites and the capital-owning class who pay the wages of workers and set the prices of goods. The political class is thereby given responsibility for the outcomes they negotiate on behalf of those who elect them.

Anthropologist David Graeber and economist Michael Hudson have both detailed how since ancient times, astute elites understood the need to limit the exploitative and inequality-generating functions of financial elites in order to maintain social order for the common good. This often took the form of debt jubilees, or cultural and religious prohibitions on lending with interest, in recognition of the turbulent consequences of populations being pushed too far into debt bondage.

Since the 1970s the political and capitalist elites have reneged on higher living standards as a pillar of the social contract. Instead of the productivity gains of technological advancements leading workers to a Jetsons-like world of expanded leisure time and/or higher pay for the same amount of work, the capital-owning class has stagnated real wages, and held on to the extra profits derived from productivity gains. Those profits have been largely funnelled into asset purchases (property and stocks) and investment income, which fuels price inflation and does not create jobs.

As a result inequality is growing and workers must work more for pay that is increasingly inadequate to live on. In the United States for example, between 1960 and 2017, median home prices increased 121% nationwide, but median household income increased by only 29%.

In addition to wage stagnation, inequality is being exacerbated by lower taxation on corporations and investment income, and deliberate inflation to cover the flaws in debt-based growth – particularly since the 2008 Global Financial Crisis. Historically, inequality is a critical marker for the stability of any political order, not only because of its impact on financially stability, but also because of its impact on individual and collective psychology.

Declining living standards stress individual and collective psychological health by pushing people down Maslow’s hierarchy of needs to a focus on physiological needs and safety. This contributes to short-term and survival-driven mindsets, and to greater individualism in a (Western) society where material conditions have become isolated from any corresponding spiritual, moral, or communal values.

Accordingly, as Western political elites have not fulfilled their end of the social contract established since the Second World War, most Western populations are losing trust in the contract.

Since the 1960s, trust in government in the United States has declined from over 70%, to a record low of 16% in 2023 according to Pew polling. In Europe, the decline is less drastic yet still serious. Despite careful OECD wording to soften the reality, the majority of citizens no longer trust the principle of democratic representation.

Results from the survey… illustrate that governments could do better in responding to citizens’ concerns. Just under four in ten respondents… say that their government would improve a poorly performing service, implement an innovative idea, or change a national policy in response to public demands. And when considering more overtly political processes, around a third of citizens say the political system in their country lets them have a say.

– Building Trust to Reinforce Democracy: Main Findings from the 2021 OECD Survey on Drivers of Trust in Public Institutions

Read differently, two-thirds of citizens say the political system does not let them have a say, and that more than 60% do not believe their government would change policy in response to public demands.

The social contract is breaking. More worrying than the reality of this challenge though are the elite responses to it which seem set on denying responsibility and gaslighting citizens’ reality.

Instead of recognising expressions of popular discontent on economic and moral issues, twenty-first century Western politicians have become more and more brazen in ignoring the public. Key events have included the 2003 invasion of Iraq, the Occupy Movement, Brexit, the election of Donald Trump, and now protests against Israel’s genocide in Gaza.

In the US and UK, growing economic disparity caused by neoliberal economic reforms since the 1980s led to populist movements in support of Donald Trump and Brexit. Both countries’ economic and political elites responded to the outcomes by branding voters as ignorant racists.

Economic and political elites treat their populations with disdain, and frequently ignore their interests and wishes. This is revealed by use of terms such as ‘fly-over states’ and Hillary Clinton’s famous reference to Trump supporters as a ‘basket of deplorables’.

Both Brexit and Trump’s 2016 victory were blamed on ‘racism’ including opposition to immigration. Clinton also appealed to victimhood by claiming people didn’t vote for her because she is a woman.

Mainstream political narratives mostly fail to acknowledge the fact that private businesses and corporations are the primary beneficiaries of mass migration which represses wages through increased labour force competition from workers who have restricted legal rights.

The same blindness to responsibility is easy to spot in elite European institutions. Even when trying to point out how Western elites have lost the trust of their populations, the European Council on Foreign Relations couldn’t help but continue the snide dismissal of lower and middle class concerns when dissecting the Brexit vote.

“The British people have spoken. They have clearly said, “We want to leave the European Union.” But beyond that, their accent is so thick that we only have the faintest idea why they did it or what they intend to do next.

What we know is that, like turkeys voting for Christmas, the British have opted to weaken their economy, reduce their international standing, and create massive uncertainty at a time when the world really doesn’t need it. All in the name of the abstract concepts of “independence” and “sovereignty.” [Emphasis added]

The elite mindsets on display ignore the concept of democracy as a means of representing citizens interests. Elite attitudes also reflect their globalised (rather than purely domestic) interests.

Beyond blunt insults about the accents of disenfranchised Northern UK districts which voted strongly for Brexit, the above statement implies that somehow tradesmen and factory workers in Liverpool owe a contribution to, or are somehow partly responsible for ‘global certainty’ (most likely a reference to financial certainty).

“It is, after all, rather extraordinary that more than half the voting population defied a large majority of its own elected parliament, all of the traditional political parties, and virtually every important institution in the country — from the Central Bank to the leaders of industry to the trade unions.”

This passage seems to invert of the concept of democracy where parliamentarians and public institutions are supposed to reflect their citizens’ views, rather than citizens being told what to think by politicians. The ECFR also inaccurately lumps UK trade unions – which showed a willingness to recognise legitimate concerns and responsibility for the Brexit vote – in with the opposing interests of the capitalist class.

Inability to recognise responsibility for actions which lead to undesirable outcomes prevents even well-meaning actors from understanding the dynamics of an issue.

The ECFR continues:

“It is hard to convince people that you will address their concerns if they don’t believe anything you say — even when you have impressive charts and data to back up your claims.

Elites across Europe and North America will need to move beyond evidence and demonstrate real empathy with the problems of their constituents if they are to remain in power.

They will have to find a way to validate the concerns of their constituents on issues such as immigration and economic insecurity without gutting their own principles.”

This exemplifies the ECFR’s inability to see that it was not the ‘inadequate communication of elite policies’ driving declining trust in the social contract, but the policies themselves. The author fails to see that the evidence disenfranchised classes need is the reality of better living standards, not empathy from people who live in another reality.

Again, the reference to ‘their own [elite] principles’ indicates that elite principles –indistinguishable from elite interests – are somehow superior to the will of the population in determining the direction of governance.

On a deeper level this public relations approach to managing the social contract is symptomatic of the worsening image-based nature of Western society. It is not who you are, the validity of your arguments, or how you behave that matters, merely how you appear via crafted imagery.

Unlike ancient rulers who sought to relieve pressure on the public via debt jubilees – primarily out of their self-interested wish to stay in power – current political elites are becoming blunter in their denial of democratic responsibility.

In September 2022 the Greens MP and Foreign Minister Annalena Baerbock unashamedly trashed the whole principle of Western democracy when declaring her undying allegiance to the war effort in Ukraine.

“If I give the promise to people in Ukraine – ‘We stand with you, as long as you need us’ – then I want to deliver. No matter what my German voters think, I want to deliver to the people of Ukraine,” said Baerbock.

Baerbock and her government colleagues (who are supposed to be working for Germans) followed their words with policies that have actively worsened living standards for Germans. One year into the war, the German Chamber of Industry and Commerce estimated the German economy had lost wealth equivalent to around €2,000 for every individual. German government policies have made energy far more expensive for German consumers, forcing a wave of German firms to move to the U.S., where they are offered subsidies and cheap energy.

US Senators have also been blunt about their continued funding for the war in Ukraine being primarily beneficial to US arms manufacturers, while their domestic population becomes more impoverished.

Corporate capture means State “vulnerability to conflicts of interest and corruption are a feature, not a bug” of Western capitalism. However this has now gone beyond obvious revolving door practices and ideological capture into real financial bondage.

Economist Gary Stevenson explains how lazy economics, lax regulation and declining corporate taxation have bonded the state to private interests, made the act of providing public services more expensive, and driven the transfer of ownership of essential services and infrastructure from the State to corporations.

After a steady decline over the previous 40 years, by 2010, when Western governments went into massive debt to bail out the risky gambling of the finance industry, the percentage of U.S. and U.K. government wealth (asset ownership) dropped below zero. This means that those governments have debts to private lenders bigger than their assets, with the same implications that private indebtedness entails.

To pay these debts and continue providing public services, governments are being forced to raise taxes on the lower and middle classes while simultaneously cutting the funding needed to maintain the quality of those services, furthering the strain on the social contract. At the same time, the Tax Justice Network estimates that the world loses $312 billion in corporate tax avoidance and $171 billion in individual tax avoidance annually.

On the psychological front however, the corporate capture and retreat of the state from its role as a binder of the community has exacerbated the West’s underlying trend towards individualism that began with the Protestant reformation.

The process of rural-urban migration and the breakdown of communal identity into individual units of labour began with the emergence of capitalism and the industrial revolution. In earlier phases of industrial capitalism, corporations were still located in a place and tethered to a community of workers that served them. In many instances they provided services such as hospitals, sports teams, vacation facilities, and schools for their workers.

However the free international movement of corporate capital since the 1980s has dissolved this final semblance of corporate communal responsibility in most of the West, though it still exists in places like Japan and South Korea. Corporations now have no responsibility to a community and are free to extract maximum profits from labour while avoiding taxes.

Where Western citizens were once bonded to a community and had a sense of belonging through rural, religious, and regional identities, most Westerners now live in secular, anonymised, and individualised urban centres with little community bonding other than via the nation-state.

Without the protection of the State, both economically and socially, Western citizens have been left floating as isolated individuals solely defined by their productive value and ability to compete in a global labour market. The digital nomad phenomenon is largely an example of middle-class Westerners seeking to leverage their privileged passports for a better standard of living on the same wages that would not suffice in their home countries.

As free-floating economic units, Westerners increasingly experience social and economic life characterised by prisoner’s dilemma decision-making – where individuals make choices that are beneficial to the individual in the short term but detrimental to the collective in the long-term. These lives are mentally, economically, and physically sicker and less resilient than lives characterised by strong social ties and sense of belonging.

Stevenson shows how prisoner’s dilemma dynamics have even begun to subtly erode the concept of “working so that our children can have a better life”, where more and more individuals are put in a position to make economic decisions that will benefit the current generation but impoverish their children and grandchildren.

So yes, the West is losing grip on the socio-economic pillars which have formed its current conception of itself – and Western leaderships are mainly to blame. The hollowing out of Western middle classes will continue to impoverish collective psychology and drive desperate popular responses – both in the ballot box and on the streets – as living standards decline and push individuals into resource scarcity and defensiveness.

Forget external boogeymen; the locus of responsibility for erosion of moral, economic, and psycho-social structures is found in the West itself. This is our moment of maturation as a civilisation. Former big-tech engineers, and co-founders of the Centre for Humane Technology Aza Raskin and Tristan Harris have described the choices we face as the end of our adolescence.

The answers are well known – living up to professed morality, creating economic structures that sustain us in the long-term and recognise our shared human interests, and creating communities of purpose and belonging. As democracies we have the chance to take responsibility for that, or continue to deepen our victimhood and watch our current world crumble around us.

thanks Alex.. This is a well argued piece.